The most important thing to understand about the internet is that it has stopped being a separate place. In the early days, we thought of it as a frontier where the physical rules of geography didn’t apply. But as the internet became the operating system for society, it inherited all the problems of the physical world, plus a few new ones. One of those problems is sovereignty.

We have a very clear idea of what a border is in physical space. If a foreign power wanted to send millions of agents into the United States to commit small-scale fraud, disrupt elections, and spread psychological operations, we would stop them at the border. We wouldn’t call it “censorship” or “isolationism.” We would call it national security. We understand that for a society to function, it needs a controlled perimeter. You can’t have a house if anyone can walk through the walls at any time.

Yet, online, we have no walls. We allow any state actor, no matter how hostile, to have direct, high-speed access to the minds of our citizens. If Russia or China wants to run a massive influence operation, they don’t need to sneak spies past the TSA. They just need a server and an algorithm. We are essentially running a country with the front door wide open in the middle of a high-crime neighborhood and wondering why our things keep going missing.

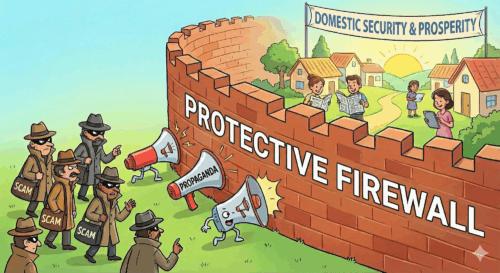

The standard objection to a “Great Firewall” is that it’s what authoritarian regimes do. It feels un-American. But that’s a confusion of categories. A firewall is just a tool. If an authoritarian regime uses a firewall to keep its people in, that’s bad. But if a free society uses a firewall to keep malicious foreign actors out, that’s defensive. It’s the difference between a prison wall and a home’s exterior wall. One is meant to strip you of freedom; the other is meant to protect the space where you exercise it.

Most of the noise on the American internet today isn’t organic. A huge percentage of the scams, the spam, and the most divisive political “discourse” is manufactured in places that don’t wish us well. These aren’t just annoying pop-ups; they are a form of low-grade, constant attrition against our social trust. When you can’t tell if you’re talking to a neighbor or a bot in a warehouse in St. Petersburg, the foundation of a democratic society starts to crumble. Trust is the most valuable resource a country has, and we are letting foreign entities strip-mine it for free.

If we want to preserve the parts of the internet we actually value—the commerce, the connection, the innovation—we have to protect the environment they grow in. Controlling our digital borders isn’t about stopping Americans from speaking; it’s about stopping foreign governments from shouting over us. We already control who enters our physical territory because we know that unrestricted entry is unsustainable. It’s time we applied that same common sense to our digital territory.